Adam

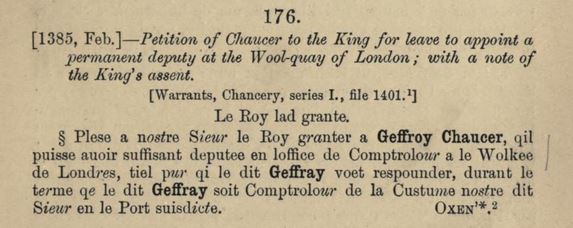

A reproduction of Chaucer’s 1385 petition is published in The British Inheritance: A Treasury of Historic Documents, from which the following images were made. The caption to the reproduction states in part: “It is probable that one of these hands is Chaucer’s, but it is impossible to say which.” (p.31) This is clearly mistaken.

Although there are no positively known samples of Chaucer’s handwriting with which to compare, the text of the petition was probably not written by Chaucer, but by a hired public scrivener, possibly by the name of Adam Pinkhurst.

This identification is the conclusion of Chaucer scholar Simon Horobin based on his paleographic analysis of the petition, as well as other scholarship identifying Pinkhurst as a scribe who worked on the earliest extant copies of Chaucer’s poetry. Pinkhurst is known to have been a member of the scrivener’s company guild in London, and probably was employed to copy or write a variety of document types, some requiring the use of the functional and terse court-hand seen in Chaucer’s petition, as well as a more literary hand. Chaucer presumably went to the shop of this scrivener with a draft, to have it written out in a professional manner.

An additional piece of literary evidence put forward for the identification is a short poem by Chaucer from this time period “Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn”:

Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee bifalle,

Boece or Troylus for to wryten newe,

Under thy long lokkes thou most have the scalle,

But after my makyng thow wryte more trewe;

So ofte adaye I mot thy werk renewe,

It to correcte and eke to rubbe and scrape,

And al is thorugh thy negligence and rape.

I wonder if Chaucer had also to correct his scribe, clearly accustomed to writing quickly, when he produced his petition.

Robert

The writer of the notification of the king’s assent, above the text of the petition,

and the signature below,

was Robert de Vere, ninth earl of Oxford. De Vere was Chamberlain of England, and the eighteen-year old king’s close political ally and recipient of largesse. In converting the petition to a warrant for the issue of letters patent under the great seal he was acting in a secretarial capacity for the king. He uses the name Oxen, short for Oxenford, and includes a scribbled graphic element. In Life-Records this is described merely as an asterisk, a description repeated by every other writer on the subject. Upon close examination however, and visible in other examples, one can see it is a five-pointed star, in heraldic terminology a “mulet”. The Earl of Ox[en]ford uses it here as an emblem representing his family name of De Vere, who held a hereditary claim to the office of Chamberlain of England.

The star is a prominent and famous element of the De Vere coat of arms. There are at least two stories in which this mulet plays a leading role. The first is the 11th century origins of the De Vere star, a legendary episode of the crusades, in which an army is saved by God’s intercession on behalf of the Christian crusaders, shining a saving light on the standard of Audrey de Vere on a night of fighting near Antioch. The second, more absurd episode occured during the Wars of the Roses. At the foggy Battle of Barnet in 1471 an army mistook the flags of its ally (a De Vere) for that of its enemy, fumed at the sight of white roses (or perhaps splendorous suns), attacked their ally, and the battle turned.

Bibliography

Crow, Martin Michael, Clair Colby Olson, and John Matthews Manly. Chaucer Life-Records. [Austin]: University of Texas Press, 1966.

Gillespie, Alexandra. “Reading Chaucer’s Words to Adam.” The Chaucer Review. 42.3 (2008): 269-283.

Horobin, Simon. “Adam Pinkhurst, Geoffrey Chaucer, and the Hengwrt Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales.” The Chaucer Review. 44.4 (2010): 351-367.

Hulbert, J R. “Chaucer and the Earl of Oxford.” Modern Philology. 10.3 (1913): 433-437.

Mooney, Linne R. “Chaucer’s Scribe.” Speculum. 81.1 (2006): 97-138.

Prescott, Andrew. “Administrative Records and the Scribal Achievement of Medieval England.” in Edwards, Anthony S. G, and Orietta Da Rold, eds. English Manuscript Studies, 1100-1700: Volume 17. London: The British Library, 2012.

Prescott, Andrew, and Elizabeth M. Hallam. The British Inheritance: A Treasury of Historic Documents. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1999.

links:

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/jul/20/highereducation.books